Saints

St. Hilda of Whitby – Catholic Education Today

“He that shall do and teach, he shall be called great in the kingdom of Heaven.” (Matthew, Ch. 5, v. 19.)

The seventh century in England, when that island was not yet united into one nation but broken up into what were called petty kingdoms, was a period of history famous for the number of the kings, princes and princesses who embraced the religious life. It was also a time, strangely enough, when monasticism, with its accompanying interest in Christian scholarship: was still in its infancy.

The seventh century in England, when that island was not yet united into one nation but broken up into what were called petty kingdoms, was a period of history famous for the number of the kings, princes and princesses who embraced the religious life. It was also a time, strangely enough, when monasticism, with its accompanying interest in Christian scholarship: was still in its infancy.

This mode of religious life had been brought from Iona in 563 through the intervention and missionary activity of St. Columba. Shortly thereafter the year 596, it arrived from the Continent with St. Augustine and his four companions, who brought their brand of monasticism to what we know today as the British Isles.

There are countless saints of this period whose relics and whose memory have been almost obliterated by the Protestant Revolt of the sixteenth century. Many of these saints were women. St. Werburgh, the daughter of the King of Mercia, who died in 699, first entered the convent at Ely near Cambridge where the abbess was another Saint, St. Audrey. King Ethelred eventually made St. Werburgh Abbess of all the religious houses of women in his Kingdom. Then there was St. Eanswide who died in the year 650, and was the daughter of King Eadwald. She founded a monastery on the shores of Kent. Another great saint of this century in England was St. Winifred from North Wales who consecrated her life to God and spent most of her life at the convent she had established at Guthurin.

Biography of St. Hilda of Whitby

All of these saints of seventh century England were the contemporaries of another great Saint whose life and works spanned the greater part of that century, St. Hilda of Whitby, convert, abbess and saint, who epitomizes for the modern woman what her role must be in her own personal education, the profession of teaching, lay and religious, the advancement of higher learning on a Catholic level, and the fostering of Christian literature in our contemporary society.

This early, and almost forgotten English Saint is indeed an appropriate model in these aspects of Catholic culture, for she is termed by scholars as the “Mother of Christian Education” and she is regarded by many others as the “Mother of English Literature”. The timeliness of the principles she advocated is evident in the similarity of her age with ours, for each age can be called a time of beginnings. The seventh century in which she lived and founded her famous double monastery of learning on the rocky coast of Britain at Whitby, was a time of conversion of individuals, families and whole races, from paganism to Christianity. It was a period of synthesis of invading tribes and peoples into a common nation with a common tradition and language. It was also an age in which education and higher learning flourished under the aegis of Christianity, a process in which St. Hilda of Whitby played such a prominent role.

According to the Chronicles of Bede, Hilda was born in the year, 614, of noble parents in the Northumberland country. Her father was Hereric, nephew to St. Edwin, King of Northumbria.

A powerful example of unwavering faith

Tragedy, however, marked her infancy, for her father was banished from his homeland by the hostile Britons, lived as a fugitive and finally died by poisoning. In the year 627, when Hilda was about fourteen years of age, with King Edwin, her uncle, and all his people, she was baptized into the Catholic Faith by St. Paulinus on Easter Sunday. This new faith occupied her entire mind and spirit and we are told that after this conversion she led an unusually devout life.

Tragedy, however, marked her infancy, for her father was banished from his homeland by the hostile Britons, lived as a fugitive and finally died by poisoning. In the year 627, when Hilda was about fourteen years of age, with King Edwin, her uncle, and all his people, she was baptized into the Catholic Faith by St. Paulinus on Easter Sunday. This new faith occupied her entire mind and spirit and we are told that after this conversion she led an unusually devout life.

The new Faith of Northumbria, however, was to have its test, for in the year 633, the King of the Britons rose in rebellion and slaughtered great numbers of the Northumbrian Christians. King Edwin, himself, was killed in the battle of Heath field in that same year. At the beginning of this persecution, which continued for quite a number of years, Hilda was about nineteen years of age. Her relatives fled from Whitby to Kent, but Hilda chose to remain behind with the possibility of martyrdom constantly before her.

After some years, however, her great religious fervor and her ambition to embrace the religious life prompted her to leave her native land, and go to the kingdom of East Anglia, where her cousin, King Annas, a very religious man, reigned as monarch. From there she went to Chelles, France, where she spent a year with her sister, Hereswide, who was a member of a religious order.

The following year, after her sister’s death, Bishop Aidan of Lindisfarne, later canonized as St. Aidan, called Hilda to return to her native Northumbria, where he finally succeeded in settling her with a small group of friends in a nunnery on the river Were. There, Hilda lived the monastic life for one year, and then she was made Abbess of a large monastery at a place which is now called Hartlepool in the bishopric of Durham.

Establishing the great Whitby monastery

Hilda was about thirty-five years of age at the time and the year would have been about 649. After several small establishments, St. Hilda was finally called to establish a great double monastery at Streaneschalch in Yorkshire, one monastery for men and the other for women.

The site of this famous double monastery, presently called Whitby, was on a high headland, three hundred feet above the sea. In the sixth and seventh centuries, there were three types of schools,-the parochial, the cathedral, and the cloistral, all classified according to their association with some phase of the Church’s religious and administrative life.

In all were taught the seven sciences of grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music, with religion, of course, as the primary subject. The double monastery school at Whitby Abbey, under St. Hilda’s guidance, was classified as a cloistral school, and became famous throughout the entire Christian world for its scholarship and learning. In the annals of contemporary writers it is stated that Whitby was a “happy place, and all who desired to be instructed in sacred reading had masters on hand to teach them.”

At Whitby Abbey, as this great seventh century educator and Saint instructed those about her, she became a student, herself. She welcomed and conversed with scholars from Rome, Carthage and Tarsus. Her students in the monastery for men and the nunnery for women, were so well-instructed in theology and the sacred sciences, that among the members were found who were considered sufficiently prepared for the reception of Holy Orders.

As a matter of fact, five bishops were consecrated from the monastery at Whitby, and a sixth would have been consecrated except for an untime ly death. The great monk, Caedmon, was a student here and became, through Hilda’s encouragement, one of the early great names in the history of English Literature. The ability and accomplishment of Hilda as a scholar in Sacred Theology and Scripture is manifest in the lives and works of her disciples, and is clearly evident in the great work of translating, copying and illuminating the books of Sacred Scripture, which took place at Whitby during her lifetime and thereafter.

The holy Abbess, Hilda, excelled in all the virtues but was eminent in the virtue of prudence. She had a particular talent for reconciling differ ences and maintaining peace among the members of her community. Kings and princes knew the greatness of her wisdom and they did not hesitate to seek her advice, which they carefully followed in many difficult affairs of government. Ecclesiastics and bishops valued her wisdom, and once she even played hostess for a Church Synod which was held at Whitby.

Prior to her death St. Hilda founded another monastery at Harkness thirteen miles from Whitby. She suffered for six years from a violent fever, and after thirty-three years in religion, St. Hilda of Whitby died at the age of sixty-six, on November 17, 680.

Reflection on the life of St. Hilda of Whitby

If we follow the pattern of Hilda’s life, it is evident that in the first place she sought to educate herself, a process which she never discontinued, and then, through her influence, she sought to communicate the scholarship at Whitby Abbey and the principles of Christian education to her disciples, who carried the torch of this monastic learning to others. The modern Catholic woman has the obligation of being well-informed for we are living in an age, like Hilda’s, when paganism, atheism and false beliefs are still more predominant than Christianity.

In the world at the present time, according to fairly reliable statistics, there are approximately 5 billion non-Christians, and there are approximately 2.4 billion Christians, which includes Catholics, Protestants and Orthodox Catholics, Of this number, there are roughly 1.2 billion Catholics in the world. Christ gave the obligation to all, men and women alike, to “teach all nations”. We cannot bring the truth to others if the truth is not sufficiently acquired by ourselves.

If anyone has not had or will not have the opportunity of fulfilling an extended formal education in their life, then they still has the obligation of accumulating through a process of self-education all the information one can acquire over a period of years in helping to enlighten others. This, of course, can be accomplished by a judicious program of reading, attending Lectures, and series of talks that might be given in her parish, or sponsored by various diocesan groups.

The Catholic Church has always encouraged the education of all people. Circumstances have sometimes made it impossible to accomplish this purpose through the course of history, but the Church has certainly never opposed the education of mankind in general. The directive contained in the spiritual work of mercy -“to instruct the ignorant”, applies to both sexes and all races of mankind. The education of the young which has always occupied the attention of the Teaching Church was never restricted to the male population.

When we compare our present methods of education, however, with those founded in the true Christian tradition, as Whitby was, there are glaring differences. In too many cases, the college students of today has been given too strictly an academic training with no regard to the life they will be leading after graduation, no spiritual quality to guide them, and no study of the role they must assume society. These important components are always emphasized in a Catholic college on a sociological and theological parity.

Catholic Education in America Today

Hilda of Whitby, in a sense, was self-taught, and she was also an educator and teacher. Down through the centuries, thousands of women like her have dedicated their lives to religion and have carried the inextinguishable fire of learning to others: St. Angela Merici, foundress of the Ursulines; St. Julie Billiart, foundress of the Sisters of Norte Dame de Namur; Mother Fontbonne, foundress of the Sisters of St. Joseph; St. Louise de Marillac, foundress of the Sisters of Charity, and our beloved Mother Elizabeth Seton who can rightly be called the originator of the parochial school system in the United States.

It can safely be assumed that the majority of present day public school teachers are women. For a Catholic teacher in a public school there are indeed many problems, but there are also many opportunities to accomplish a great deal of good, even if religion is not a formal part of the curriculum. In this dedicated but also very underpaid profession today the teacher has a chance to mold their students in a very Christ-like way; to increase their thirst for real knowledge and truth; to inculcate right moral principles, and help form the character of her students not only by good example but by personal interest in their work as well.

St. Bonaventure emphasized the influence when he said: “The only true educator is one who can kindle in the heart of his pupil the vision of beauty, illumine it with the light of truth and infuse virtue.” This directive is most important today for all in the teaching profession when the education of youth is so beset by irreligious and harmful influences.

In ancient Greece, Aristotle, the great philosopher phrased the wise words: “They who educate children well are more to be honored than they who produce them.” There is no doubt that teachers should be held in great esteem for the burdensome task they perform but they should likewise consider it an honor and privilege to serve in this God-given vocation. Pope Pius XII voiced this sentiment in the “Duties and Rights of Catholic Teachers” when he said: “What an honor to be the delegates and representatives of the parents in accomplishing such a mission in their name. But if teachers have the assurance of receiving this mission from God, at the same time what trepidation they must experience in considering the dignity, the consequences, the responsibilities, the difficulties and the self-sacrifice which this mission entails”.

The Challenges of Catholic Education Today

When we compare our era with any other age in the history of man no more important problem exists in our day than education according to the principles laid down by Christ, Himself, if His Gospel is to reach all men and help them save their immortal souls. Many communities are torn by debates about the kind of education we should give our children, about the place of religion in the curriculum, and about the financial remuneration of the people who give themselves to this important work.

There is no doubt that many gifted teachers in the primary and secondary schools are leaving the teaching profession as a result of low salaries and associating themselves with other fields of work. The modern Catholic has the serious obligation not only to be educated themselves but also to that training either through their chosen profession of teaching or by their thoughtful participation in community discussions to determine that God will be kept in education and that teachers will receive a just wage. If one displays little or no interest in this vital work, then one cannot convey this interest to others, for no one can give what he does not possess.

The Lasting Impact of St. Hilda of Whitby

St. Hilda of Whitby, a woman of the past but very much an intellectual woman according to our modern standards, the pioneer of all Catholic women in self-education and teaching-will always be an inspiration for women of every century in this Christ-like task of helping to form the minds and opinions of others. From her citadel of learning and culture on the rockbound coast of England her influence helped spread Christianity and learning throughout the world of her day.

The knowledgeable Catholic of today can perpetuate this same Christian influence if one imitates this great saint as an educator, writer, and patron of all that is good and God-like in literature, and if she helps spread the Doctrine of Christ upon earth. Then the words found in the Book of Daniel the Prophet, so applicable to the great Abbess of Whitby will redound to her eternal praise: “Those who teach many unto justice will shine like stars for all eternity“.

PRAYER TO ST. HILDA OF WHITBY:

O Lord and Teacher of all wisdom, Jesus Christ, who raised up the holy abbess Hilda to help bring the flame of Thy knowledge and teachings to the world, grant that we may be imbued with the same love of Thy law and Thy holy gospels, that we may rejoice with Thee for all eternity: Who livest and reignest, world without end. Amen.

O God, whose blessed Son became poor that we through his poverty Might be rich: deliver us from an inordinate love of this world, that, following the example of your servant Hilda, we may serve thee with singleness of heart, and attain to the riches of the world to come; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever.

O God of peace, by whose grace the abbess Hilda was endowed with Gifts of justice, prudence, and strength to rule as a wise mother over the nuns and monks of her household, and to become a trusted and reconciling friend to leaders of the Church: Give us the grace to respect and love our fellow Christians with whom we disagree, that our common life may be enriched and your gracious will be done, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever.

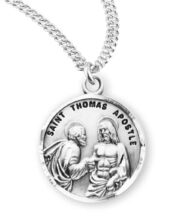

St. Thomas the Apostle Patron Saint Medal - Round - 20 Inch Chain

St. Thomas the Apostle Patron Saint Medal - Round - 20 Inch Chain